|

| 1 | +# pycobytes[32] := Recursive Laziness |

| 2 | +<!-- #SQUARK live! |

| 3 | +| dest = issues/(issue)/32 |

| 4 | +| title = Recursive Laziness |

| 5 | +| head = Recursive Laziness |

| 6 | +| index = 32 |

| 7 | +| tags = syntax |

| 8 | +| date = 2025 June 12 |

| 9 | +--> |

| 10 | + |

| 11 | +> *In theory, theory and practice are the same. In practice they are different.* |

| 12 | +

|

| 13 | +Hey pips! |

| 14 | + |

| 15 | +Last time we looked at the tricky topic of generators. |

| 16 | + |

| 17 | +```py |

| 18 | +def find_flagged_users(users): |

| 19 | + for user_id in users: |

| 20 | + user = find_user(user_id) |

| 21 | + if user.expired or user.flags.size > 0: |

| 22 | + yield user |

| 23 | +``` |

| 24 | + |

| 25 | +That there is a generator function since it uses `yield`. Let’s turn it into an equivalent generator expression: |

| 26 | + |

| 27 | +```py |

| 28 | +flagged_users = ( |

| 29 | + find_user(user_id) |

| 30 | + for user_id in users |

| 31 | + if user.expired or user.flags.size > 0 |

| 32 | +) |

| 33 | +``` |

| 34 | + |

| 35 | +Now `flagged_users` stores a generator object. We can find its values by iterating over it: |

| 36 | + |

| 37 | +```py |

| 38 | +>>> for user in flagged_users: |

| 39 | + print(user.name) |

| 40 | +Bob |

| 41 | +Jeff |

| 42 | +Rick |

| 43 | +``` |

| 44 | + |

| 45 | +Coolio. Now let’s suppose we wanted to iterate over it again, this time in a set comprehension: |

| 46 | + |

| 47 | +```py |

| 48 | +>>> {*user.flags for user in flagged_users} |

| 49 | +set() |

| 50 | +``` |

| 51 | + |

| 52 | +Huh – An empty set? What happened to our users? |

| 53 | + |

| 54 | +This is the other quirk of generators. Remember that they’re lazy-loading, so they only compute each on the fly as they’re iterated over. When iteration reaches the end, the generator is **consumed**. At this point, further iteration won’t do anything. |

| 55 | + |

| 56 | +```py |

| 57 | +>>> gen = (i for i in range 4) |

| 58 | +>>> l = list(gen) # constructing a list iterates over its input |

| 59 | +[0, 1, 2, 3] |

| 60 | +>>> s = set(gen) # as does constructing a set |

| 61 | +{} |

| 62 | +``` |

| 63 | + |

| 64 | +Attempting further iteration raises the `StopIteration` exception (which is what tells a `for` loop when to stop!). |

| 65 | + |

| 66 | +```py |

| 67 | +>>> next(gen) |

| 68 | +Traceback (most recent call last): |

| 69 | + File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> |

| 70 | +StopIteration |

| 71 | +``` |

| 72 | + |

| 73 | +This is super important – generators can only be used once.[^once] That’s the main tradeoff between a `list` and a generator. If you plan on reusing, mutating and/or passing the collection around, stick to a `list`. If you only need the items one-by-one as they come in, like when handling a task queue, a generator can be more performant. |

| 74 | + |

| 75 | +[^once]: *once in their entirety. |

| 76 | + |

| 77 | +```py |

| 78 | +def process_list(data: list): |

| 79 | + n = len(data) |

| 80 | + highest = max(data) |

| 81 | + |

| 82 | + return [(each - highest)**2 for each in data] / n |

| 83 | + |

| 84 | +def process_gen(data: Generator[]): |

| 85 | + for each in data: |

| 86 | + score += each ** 0.5 |

| 87 | +``` |

| 88 | + |

| 89 | +A good example of this is when using the built-in Python iterable functions, like `len()`, `sum()`, `max()`, `zip()` – yeah, those. They can take any kind of iterable, so a generator works just fine for them! Why expend overhead and memory constructing a list, and only then passing it to the function, when you can just let the function grab the values as it needs them? |

| 90 | + |

| 91 | +```py |

| 92 | +# unnecessary list |

| 93 | +>>> sum([player.hours for player in data]) |

| 94 | +1679 |

| 95 | + |

| 96 | +# cleaner and faster |

| 97 | +>>> sum(player.hours for player in data) |

| 98 | +1679 |

| 99 | +``` |

| 100 | + |

| 101 | +Notice the generator expression’s kinda ‘embedded’ inside the parentheses of the function call, so you don’t need an extra pair like `sum((player.hours for player in data))`. That would be, well, horrific. |

| 102 | + |

| 103 | +> [!Tip] |

| 104 | +> For small collection sizes, this is totally a micro-optimisation. Negligible impact on performance, lmao. But hey, it does improve readability! |

| 105 | +

|

| 106 | +One more thing it’s good to just be aware of – how you can write nested generator functions. It’ll unlikely you’ll ever need them unless you’re doing some, idk, strange tree exploration. But cool to have in your toolkit. |

| 107 | + |

| 108 | +Regular functions return just 1 object, but generator functions return a generator with multiple objects. So, if we had a generator function which wanted to call another generator inside it… |

| 109 | + |

| 110 | +```py |

| 111 | +def pos_ints(): |

| 112 | + for n in itertools.count(1): |

| 113 | + yield n |

| 114 | + |

| 115 | +def naturals(): |

| 116 | + yield 0 |

| 117 | + yield pos_ints() # <-- careful with this line! |

| 118 | + yield float("inf") |

| 119 | +``` |

| 120 | + |

| 121 | +If we get the output of this, it’s not the entire sequence, but just 2 objects: |

| 122 | + |

| 123 | +```py |

| 124 | +>>> list(naturals()) |

| 125 | +[0, <generator object pos_ints at 0x000001D142D6F420>, inf] |

| 126 | +``` |

| 127 | + |

| 128 | +That’s because the line `yield pos_ints()` is yielding the *entire* generator returned by `pos_ints()` – not the individual *values* of the generator. So, to sort of ‘unpack’ it, we need to manually iterate over it: |

| 129 | + |

| 130 | +```py |

| 131 | +def naturals(): |

| 132 | + yield 0 |

| 133 | + for each in pos_ints(): |

| 134 | + yield each |

| 135 | + yield float("inf") |

| 136 | +``` |

| 137 | + |

| 138 | +This is a bit verbose. Maybe you’d wonder why you can’t unpack the values with `*`. |

| 139 | + |

| 140 | +```py |

| 141 | +def naturals(): |

| 142 | + yield 0 |

| 143 | + yield *pos_ints() |

| 144 | + yield float("inf") |

| 145 | +``` |

| 146 | + |

| 147 | +Well, `*` has to unpack the values *to* somewhere, and a yielded value isn’t exactly a valid context. Also, this would still return the entire sequence, not `yield` the values one-by-one – it’d be pretty peculiar if this were the case: |

| 148 | + |

| 149 | +```py |

| 150 | +yield 1 |

| 151 | +yield 2 |

| 152 | +yield 3 |

| 153 | +... |

| 154 | + |

| 155 | +# would be weird if this were the same: |

| 156 | +yield *[1, 2, 3, ...] |

| 157 | +``` |

| 158 | + |

| 159 | +Instead, Python provides an intuitive keyword combo for achieving this – it’s `yield from`! |

| 160 | + |

| 161 | +```py |

| 162 | +def naturals(): |

| 163 | + yield 0 |

| 164 | + yield from pos_ints() |

| 165 | + yield float("inf") |

| 166 | +``` |

| 167 | + |

| 168 | +It’s essentially ‘passing control’ of the generator and its yielded values to this nested generator. When `pos_ints()` is exhausted, `naturals()` gets control back and proceeds to the next value, `float("inf")`. (PSA: famously *not* a number, this was for illustrative purposes only :P) |

| 169 | + |

| 170 | +```py |

| 171 | +>>> list(naturals) |

| 172 | +... |

| 173 | +# ...the sequence is infinite, lmao. |

| 174 | +``` |

| 175 | + |

| 176 | +Ok, for a better example then: |

| 177 | + |

| 178 | +```py |

| 179 | +>>> def inner(word: str): |

| 180 | + for letter in word: |

| 181 | + yield letter |

| 182 | + |

| 183 | +>>> def outer(word: str): |

| 184 | + yield from inner(word) |

| 185 | + yield "!" |

| 186 | + |

| 187 | +>>> outer("never") |

| 188 | +never! |

| 189 | +``` |

| 190 | + |

| 191 | + |

| 192 | +--- |

| 193 | + |

| 194 | +<div align="center"> |

| 195 | + |

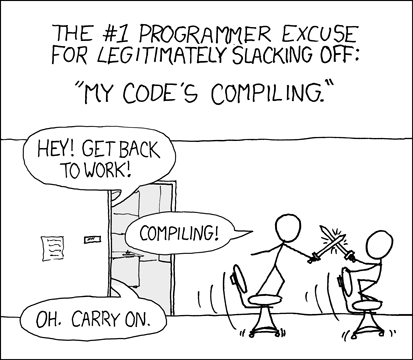

| 196 | +[](https://xkcd.com/303) |

| 197 | + |

| 198 | +[*XKCD* 303](https://xkcd.com/303) |

| 199 | + |

| 200 | +</div> |

0 commit comments