diff --git a/.DS_Store b/.DS_Store

deleted file mode 100644

index 607c799..0000000

Binary files a/.DS_Store and /dev/null differ

diff --git a/guides/.DS_Store b/guides/.DS_Store

index 5adb9de..b87b296 100644

Binary files a/guides/.DS_Store and b/guides/.DS_Store differ

diff --git a/guides/interpretation/regression-table-ex1.png b/guides/interpretation/regression-table-ex1.png

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..2c01ee6

Binary files /dev/null and b/guides/interpretation/regression-table-ex1.png differ

diff --git a/guides/interpretation/regression-table-ex2.png b/guides/interpretation/regression-table-ex2.png

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..aee8502

Binary files /dev/null and b/guides/interpretation/regression-table-ex2.png differ

diff --git a/guides/interpretation/regression-table.bib b/guides/interpretation/regression-table.bib

index 5de5b3a..596d58c 100644

--- a/guides/interpretation/regression-table.bib

+++ b/guides/interpretation/regression-table.bib

@@ -8,377 +8,26 @@

-@article{coffman_2015,

- author = {Coffman, Lucas C. and Niederle, Muriel},

- date-added = {2023-04-06 16:19:48 -0400},

- date-modified = {2023-04-06 16:20:40 -0400},

- journal = {Journal of Economic Perspectives},

+@article{albertson_2023,

+ author = {Albertson, Bethany and Jessee, Stephen},

+ date-added = {2024-03-16 10:00:00 -0400},

+ date-modified = {2024-03-16 10:00:00 -0400},

+ journal = {Journal of Experimental Political Science},

number = {3},

- pages = {81-98},

- rating = {1},

- title = {Pre-analysis Plans Have Limited Upside, Especially Where Replications Are Feasible},

- volume = {29},

+ pages = {448-454},

+ title = {Moderator Placement in Survey Experiments: Racial Resentment and the "Welfare" versus "Assistance to the Poor" Question Wording Experiment},

+ volume = {10},

year = {2015}}

-@article{monogan_2013,

- abstract = {This article makes the case for the systematic registration of political studies. By proposing a research design before an outcome variable is observed, a researcher commits him- or herself to a theoretically motivated method for studying the object of interest. Further, study registration prompts peers of the discipline to evaluate a study's quality on its own merits, reducing norms to accept significant results and reject null findings. To advance this idea, the Political Science Registered Studies Dataverse (http://dvn.iq.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/registration) has been created, in which scholars may create a permanent record of a research design before completing a study. This article also illustrates the method of registration through a study of the impact of the immigration issue in the 2010 election for the U.S. House of Representatives. Prior to the election, a design for this study was posted on the Society for Political Methodology website (http://polmeth.wustl.edu/mediaDetail.php?docId=1258). After the votes were counted, the study was completed in accord with the design. The treatment effect in this theoretically specified design was indiscernible, but a specification search could yield a significant result. Hence, this article illustrates the argument for study registration through a case in which the result could easily be manipulated.},

- author = {James E. Monogan},

- date-added = {2023-04-06 16:14:50 -0400},

- date-modified = {2023-04-06 16:16:26 -0400},

- issn = {10471987, 14764989},

- journal = {Political Analysis},

- number = {1},

- pages = {21--37},

- publisher = {Oxford University Press},

- title = {A Case for Registering Studies of Political Outcomes: An Application in the 2010 House Elections},

- url = {http://www.jstor.org/stable/23359688},

- urldate = {2023-04-06},

- volume = {21},

- year = {2013},

- bdsk-url-1 = {http://www.jstor.org/stable/23359688}}

-

-@article{anderson_2013,

- author = {Richard G. Anderson},

- date-added = {2023-04-06 16:14:50 -0400},

- date-modified = {2023-04-06 16:16:37 -0400},

- issn = {10471987, 14764989},

- journal = {Political Analysis},

- number = {1},

- pages = {38--39},

- publisher = {Oxford University Press},

- title = {Registration and Replication: A Comment},

- url = {http://www.jstor.org/stable/23359689},

- urldate = {2023-04-06},

- volume = {21},

- year = {2013},

- bdsk-url-1 = {http://www.jstor.org/stable/23359689}}

-

-@article{gelman_2013,

- author = {Andrew Gelman},

- date-added = {2023-04-06 16:14:50 -0400},

- date-modified = {2023-04-06 16:18:32 -0400},

- issn = {10471987, 14764989},

- journal = {Political Analysis},

- number = {1},

- pages = {40--41},

- publisher = {Oxford University Press},

- title = {Preregistration of Studies and Mock Reports},

- url = {http://www.jstor.org/stable/23359690},

- urldate = {2023-04-06},

- volume = {21},

- year = {2013},

- bdsk-url-1 = {http://www.jstor.org/stable/23359690}}

-

-@article{judkins_porter_2016,

- author = {Judkins, David R. and Porter, Kristin E.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 15:22:01 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 15:22:38 -0500},

- journal = {Statistics in Medicine},

- pages = {1763-1773},

- title = {Robustness of Ordinary Least Squares in Randomized Clinical Trials},

- volume = {35},

- year = {2016}}

-

-@article{angrist_2001,

- author = {Angrist, Joshua D.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 15:19:19 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 15:20:55 -0500},

- journal = {Journal of Business & Economic Statistics},

- number = {1},

- pages = {2-28},

- title = {Estimation of Limited Dependent Variable Models With Dummy Endogenous Regressors: Simple Strategies for Empirical Practice},

- volume = {19},

- year = {2001}}

-

-@article{gelman_pardoe_2007,

- author = {Gelman, Andrew and Pardoe, Iain},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 15:17:47 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 15:18:22 -0500},

- journal = {Sociological Methodology},

- pages = {23-51},

- title = {Average Predictive Comparisons for Models with Nonlinearity, Interactions, and Variance Components},

- volume = {37},

- year = {2007}}

-

-@article{stock_2010,

- author = {Stock, James H.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 15:16:43 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 15:17:15 -0500},

- journal = {Journal of Economic Perspectives},

- number = {2},

- pages = {83-94},

- title = {The Other Transformation in Econometric Practice: Robust Tools for Inference},

- volume = {24},

- year = {2010}}

-

-@article{white_1980,

- author = {White, Halbert},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 15:15:01 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 15:15:47 -0500},

- journal = {Econometrica},

- number = {4},

- pages = {817--838},

- title = {A Heteroskedasticity- Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity},

- volume = {48},

- year = {1980}}

-

-@article{angrist_pischke_2010,

- author = {Angrist, Joshua D. and Pischke, J{\"o}rn-Steffen},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 15:05:05 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 15:05:56 -0500},

- journal = {Journal of Economic Perspectives},

- number = {2},

- pages = {3-30},

- title = {The Credibility Revolution in Empirical Economics},

- volume = {24},

- year = {2010}}

-

-@article{findley_et_al_2016,

- abstract = { In 2015, Comparative Political Studies embarked on a landmark pilot study in research transparency in the social sciences. The editors issued an open call for submissions of manuscripts that contained no mention of their actual results, incentivizing reviewers to evaluate manuscripts based on their theoretical contributions, research designs, and analysis plans. The three papers in this special issue are the result of this process that began with 19 submissions. In this article, we describe the rationale for this pilot, expressly articulating the practices of preregistration and results-free review. We document the process of carrying out the special issue with a discussion of the three accepted papers, and critically evaluate the role of both preregistration and results-free review. Our main conclusions are that results-free review encourages much greater attention to theory and research design, but that it raises thorny problems about how to anticipate and interpret null findings. We also observe that as currently practiced, results-free review has a particular affinity with experimental and cross-case methodologies. Our lack of submissions from scholars using qualitative or interpretivist research suggests limitations to the widespread use of results-free review. },

- author = {Michael G. Findley and Nathan M. Jensen and Edmund J. Malesky and Thomas B. Pepinsky},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 15:03:59 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 15:04:10 -0500},

- doi = {10.1177/0010414016655539},

- eprint = {https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016655539},

- journal = {Comparative Political Studies},

- number = {13},

- pages = {1667-1703},

- title = {Can Results-Free Review Reduce Publication Bias? The Results and Implications of a Pilot Study},

- url = {https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016655539},

- volume = {49},

- year = {2016},

- bdsk-url-1 = {https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016655539}}

-

-@article{nyhan_2015,

- author = {Nyhan, Brendan},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 15:02:08 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 15:02:45 -0500},

- journal = {PS: Political Science and Politics},

- number = {S1},

- pages = {78-83},

- title = {Increasing the Credibility of Political Science Research: A Proposal for Journal Reforms},

- volume = {48},

- year = {2015}}

-

-@article{rosenthal_1979,

- author = {Rosenthal, Robert},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:25:15 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:25:58 -0500},

- journal = {Psychological Bulletin},

- pages = {638-641},

- title = {The 'File Drawer Problem' and Tolerance for Null Results},

- volume = {86},

- year = {1979}}

-

-@article{rosenbaum_1984,

- author = {Rosenbaum, Paul R.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:23:59 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:24:50 -0500},

- journal = {ournal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General)},

- pages = {656-666},

- title = {The Consquences of Adjustment for a Concomitant Variable That Has Been Affected by the Treatment},

- volume = {147},

- year = {1984}}

-

-@book{gerber_green_2012,

- author = {Gerber, Alan S. and Green, Donald P.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:21:57 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:22:59 -0500},

- publisher = {W.W. Norton},

- title = {Field Experiments: Design, Analysis, and Interpretation},

- year = {2012}}

-

-@unpublished{gelman_loken_2013,

- author = {Gelman, Andrew and Loken, Eric},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:19:15 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:20:17 -0500},

- title = {The Garden of Forking Paths: Why Multiple Comparisons Can Be a Problem, Even When There Is No 'Fishing Expedition' or 'P-Hacking' and the Research Hypothesis Was Posited Ahead of Time},

- year = {2013},

- bdsk-url-1 = {http://www.stat.columbia.edu/~gelman/research/unpublished/p_hacking.pdf}}

-

-@article{simmons_et_al_2011,

- author = {Simmons, Joseph P. and Nelson, Leif D. and Simonsohn, Uri},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:18:09 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:18:51 -0500},

- journal = {Psychological Science},

- pages = {1359-1366},

- title = {False-Positive Psychology: Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything as Significant},

- volume = {22},

- year = {2011}}

-

-@article{humphreys_et_al_2013,

- author = {Humphreys, Macartan and Sanchez de la Sierra, Raul and van der Windt, Peter},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:16:50 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:17:38 -0500},

- journal = {Political Analysis},

- pages = {1-20},

- title = {Fishing, Commitment, and Communication: A Proposal for Comprehensive Nonbinding Research Registration},

- volume = {21},

- year = {2013}}

-

-@article{greenland_et_al_2016,

- abstract = {Misinterpretation and abuse of statistical tests, confidence intervals, and statistical power have been decried for decades, yet remain rampant. A key problem is that there are no interpretations of these concepts that are at once simple, intuitive, correct, and foolproof. Instead, correct use and interpretation of these statistics requires an attention to detail which seems to tax the patience of working scientists. This high cognitive demand has led to an epidemic of shortcut definitions and interpretations that are simply wrong, sometimes disastrously so---and yet these misinterpretations dominate much of the scientific literature. In light of this problem, we provide definitions and a discussion of basic statistics that are more general and critical than typically found in traditional introductory expositions. Our goal is to provide a resource for instructors, researchers, and consumers of statistics whose knowledge of statistical theory and technique may be limited but who wish to avoid and spot misinterpretations. We emphasize how violation of often unstated analysis protocols (such as selecting analyses for presentation based on the P values they produce) can lead to small P values even if the declared test hypothesis is correct, and can lead to large P values even if that hypothesis is incorrect. We then provide an explanatory list of 25 misinterpretations of P values, confidence intervals, and power. We conclude with guidelines for improving statistical interpretation and reporting.},

- author = {Greenland, Sander and Senn, Stephen J. and Rothman, Kenneth J. and Carlin, John B. and Poole, Charles and Goodman, Steven N. and Altman, Douglas G.},

- date = {2016/04/01},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:12:41 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:14:40 -0500},

- doi = {10.1007/s10654-016-0149-3},

- id = {Greenland2016},

- isbn = {1573-7284},

- journal = {European Journal of Epidemiology},

+@article{gaikwad_2021,

+ author = {Gaikwad, Nikhar, and Nellis, Gareth},

+ date-added = {2024-03-16 10:00:00 -0400},

+ date-modified = {2024-03-16 10:00:00 -0400},

+ journal = {American Political Science Review},

number = {4},

- pages = {337--350},

- title = {Statistical tests, P values, confidence intervals, and power: a guide to misinterpretations},

- url = {https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0149-3},

- volume = {31},

- year = {2016},

- bdsk-url-1 = {https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0149-3}}

-

-@article{olken_2015,

- author = {Olken, Benjamin A.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:09:52 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:10:19 -0500},

- journal = {Journal of Economic Perspectives},

- number = {3},

- pages = {61-80},

- title = {Promises and Perils of Pre-analysis Plans},

- volume = {29},

- year = {2015}}

-

-@article{abadie_et_al_2014,

- author = {Abadie, Alberto and Athey, Susan and Imbens, Guido W. and Wooldridge, Jeffrey M.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:07:54 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:08:44 -0500},

- journal = {NBER Working Paper No. 20325},

- title = {Finite Population Causal Standard Errors},

- year = {2014}}

-

-@article{lin_2013,

- author = {Lin, Winston},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:07:03 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:07:35 -0500},

- journal = {Annals of Applied Statistics},

- pages = {295-318},

- title = {Agnostic Notes on Regression Adjustments to Experimental Data: Reexamining Freedman's Critique},

- volume = {7},

- year = {2013}}

-

-@article{samii_aronow_2012,

- author = {Samii, Cyrus and Aronow, Peter M.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:06:14 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:06:53 -0500},

- journal = {Statistics and Probability Letters},

- pages = {365-370},

- title = {On Equivalencies Between Design-Based and Regression-Based Variance Estimators for Randomized Experiments},

- volume = {82},

- year = {2012}}

-

-@article{reichardt_gollob_1999,

- author = {Reichardt, Charles S. and Gollog, Harry F.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:04:52 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:05:51 -0500},

- journal = {Psychological Methods},

- pages = {117-128},

- title = {Justifying the Use and Increasing the Power of a t Test for a Randomized Experiment with a Convenience Sample},

- volume = {4},

- year = {1999}}

-

-@article{imbens_kolesar_2016,

- author = {Imbens, Guido W. and Koles{\'a}r, Michal},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:03:51 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:04:37 -0500},

- journal = {Review of Economics and Statistics},

- pages = {701-712},

- title = {Robust Standard Errors in Small Samples: Some Practical Advice},

- volume = {98},

- year = {2016}}

-

-@article{imbens_2015,

- author = {Imbens, Guido W.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:02:21 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:02:55 -0500},

- journal = {Journal of Human Resources},

- pages = {373-419},

- title = {Matching Methods in Practice: Three Examples},

- volume = {50},

- year = {2015}}

-

-@article{imbens_wooldridge_2009,

- author = {Imbens, Guido W. and Wooldridge, Jeffrey M.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 14:01:07 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:02:00 -0500},

- journal = {Journal of Economic Literature},

- pages = {5-86},

- title = {Recent Developments in the Econometrics of Program Evaluation},

- volume = {47},

- year = {2009}}

-

-@book{angrist_pischke_2015,

- author = {Angrist, Joshua D. and Pischke, J{\"o}rn-Steffen},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 13:59:44 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 14:00:33 -0500},

- publisher = {Princeton University Press},

- title = {Mastering 'Metrics: The Path from Cause to Effect},

- year = {2015}}

-

-@article{freedman_1991,

- author = {Freedman, David A.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 13:58:32 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 13:59:18 -0500},

- journal = {Sociological Methodology},

- pages = {291-358},

- title = {Statistical Models and Shoe Leather},

- volume = {21},

- year = {1991}}

-

-@book{james_et_al_2013,

- author = {James, Gareth and Witten, Daniela and Hastie, Trevor and Tibshirani, Robert},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 12:30:14 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 12:31:42 -0500},

- publisher = {Springer},

- title = {An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R},

- year = {2013},

- bdsk-url-1 = {https://www.statlearning.com/}}

-

-@book{hansen_2022,

- author = {Hansen, Bruce},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 12:24:48 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 12:28:05 -0500},

- publisher = {Princeton University Press},

- title = {Econometrics},

- year = {2022}}

-

-@article{buja_et_al_2015,

- author = {Buja, A. and Berk, R. A. and Brown, L. D. and George, E. I. and Pitkin, E. and Traskin, M. and Zhao, L. and Zhang, K.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 12:22:54 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 12:24:09 -0500},

- journal = {Statistical Science},

- pages = {1-44},

- title = {Models as Approximations - A Conspiracy of Random Regressors and Model Deviations Against Classical Inference in Regression},

- year = {2015}}

-

-@article{berk_et_al_2014,

- author = {Berk, R. A. and Brown, L. D. and Buja, A. and George, E. I. and Pitkin, E. and Zhang, K. and Zhao, L.},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 12:20:40 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 12:21:45 -0500},

- journal = {Sociological Methods Research},

- number = {3},

- pages = {422-451},

- title = {Misspecified Mean Function Regression: Making Good Use of Regression Models That Are Wrong},

- volume = {43},

- year = {2014}}

+ pages = {1129-1146},

+ title = {Overcoming the Political Exclusion of Migrants: Theory and Experimental Evidence from India},

+ volume = {10},

+ year = {2021}}

-@book{angrist_pischke_2009,

- author = {Angrist, Joshua D. and Pischke, J{\"o}rn-Steffen},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 12:19:03 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 12:20:00 -0500},

- publisher = {Princeton University Press},

- title = {Mostly Harmless Econometrics},

- year = {2009}}

-@unpublished{asunka_et_al_2013,

- author = {Asunka, Joseph and Brierley, Sarah and Golden, Miriam and Kramon, Eric and Ofosu, George},

- date-added = {2023-02-09 12:15:45 -0500},

- date-modified = {2023-02-09 12:16:42 -0500},

- title = {Protecting the Polls: The Effect of Observers on Election Fraud},

- year = {2013}}

diff --git a/guides/interpretation/regression-table_en.qmd b/guides/interpretation/regression-table_en.qmd

index 7b8a79f..4ffb621 100644

--- a/guides/interpretation/regression-table_en.qmd

+++ b/guides/interpretation/regression-table_en.qmd

@@ -1,152 +1,90 @@

---

-title: "10 Things to Know About Reading a Regression Table"

+title: "10 Things You Need to Know About Regression Tables"

author:

- - name: "Abby Long"

- url: https://www.linkedin.com/in/abby-long-834677a

+ - name: "Eddy S. F. Yeung"

+ url: https://eddy-yeung.github.io/

image: regression-table.png

bibliography: regression-table.bib

abstract: |

- This guide gives basic information to help you understand how to interpret the results of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression in social science research. The guide focuses on regression but also discusses general concepts such as confidence intervals.

+ This guide describes how to draw out and interpret the results from an experiment when they are presented in a regression table.

---

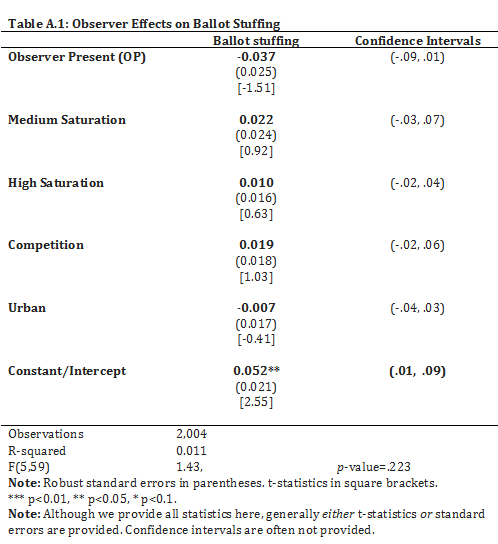

-The table below that will be used throughout this methods guide is adapted from a study done by EGAP members Miriam Golden, Eric Kramon and their colleagues [@asunka_et_al_2013]. The authors performed a field experiment in Ghana in 2012 to test the effectiveness of domestic election observers on combating two common electoral fraud problems: ballot stuffing and overvoting. Ballot stuffing occurs when more ballots are found in a ballot box than are known to have been distributed to voters. Overvoting occurs when more votes are cast at a polling station than the number of voters registered. This table reports a multiple regression (this is a concept that will be further explained below) from their experiment that explores the effects of domestic election observers on ballot stuffing. The sample consists of 2,004 polling stations.

+# What Is a Regression Table?

-

+Linear regression, a statistical technique, is often used to estimate the average effect of a treatment on an outcome in an experiment and the uncertainty around this estimate. Features of the experimental design are accommodated in the regression. In some cases, the regression also controls for pretreatment variables to improve the precision of the estimate. Output from the regression is often used to test whether there is sufficient evidence to reject the hypothesis of zero average treatment effect.

-# What is regression?

+A regression table presents the results of the regression and the choices the researcher made to produce the results. A single table may present results from multiple analyses, with each column referring to a separate analysis. Analyses might be run for multiple outcomes, subsets of data, or to assess different combinations of treatments.

-Regression is a method for calculating the line of best fit. The regression line uses the “independent variables” to predict the outcome or “dependent variable.” The dependent variable represents the output or response. The independent variables represent inputs or predictors, or they are variables that are tested to see if they predict the outcome.

+# Why Are Regression Tables Important?

-Independent and dependent variables have many synonyms, so it helps to be familiar with them. They are the explanatory and response variables, input and output variables, right hand side and left hand side variables, explanans and explanandum, regressor and regressand, predictor and criterion variable, among many others. The first thing you need to do when you see a regression table is to figure out what the dependent variable is---this is often written at the top of the column. Afterwards identify the most important independent variables. You will base your interpretation on these.

+A regression table can efficiently convey both what the study found and salient details about the experimental design and analysis procedure.

-A positive relationship in a regression means that high values of the independent variable are associated with high values of the dependent variable. A negative relationship means that units which have high values on the independent variable tend to have low values on the dependent variable, and vice versa. Regressions can be run to estimate or test many different relationships. You might run a regression to predict how much more money people earn on average for every additional year of education, or to predict the likelihood of success based on hours practiced in a given sport.

+# What Is a Regression Equation?

-Use the app below to get a feel for what a regression is and what it does. Below we will talk through the output of the regression table. Fill in values for x and for y and then look to see how the line of best fit changes to capture the average relationship between x and y. As the line changes, so too does the key information in the regression table.

+A regression equation is a mathematical formula linking the treatment to the outcome, and the simplest version is $Y_i = a + bT_i + e_i$, where $Y_i$ is the outcome variable, $T_i$ is the treatment variable, and $e_i$ is noise which we assume has a mean of 0 across all the units in our study. By convention, $T_i = 1$ when a unit is treated and $T_i = 0$ when a unit is not treated. This means that $Y_i = a + e_i$ when a unit is not treated and $Y_i = a + b + e_i$ when a unit is treated, and the difference between the two, $b$, is the treatment effect.

-

+When we run a regression, we estimate $b$, and this is our estimate of the average treatment effect of $T$ on $Y$ for the units in our study.

-# What is a regression equation?

+There is a deep connection between this simple regression equation and just taking the difference between the average outcome for treated units and the average outcome for the control units in a randomized experiment. These methods will produce the same estimate for the treatment effect for most simple designs.

-This is the formula for a regression that contains only two variables:

+A variation of a regression equation is of the following form: $Y_i = a + bT_i + cM_i + dT_i*M_i + e_i$, where $M_i$ is a moderator and all other variables are as before. The moderator could be a pretreatment characteristic of an individual unit, such as the age, gender, or race. Researchers might estimate this equation when they are interested in how the average treatment effect may differ for units with different values of the moderator. We will discuss how to interpret regressions with interaction terms in @sec-interaction.

-$$Y=α+βX+ε$$

+# How a Regression Table Is Usually Laid Out

-The Y on the left side of the equation is the dependent variable. The α or Alpha coefficient represents the intercept, which is where the line hits the y-axis in the graph, i.e., the predicted value of Y when X equals 0. The β or Beta coefficient represents the slope, the predicted change in Y for each one-unit increase in X.

+The table below, reproduced from @albertson_2023 [p. 450], is an example of a regression table of experimental results. The authors ran an online survey experiment to replicate the effect of question wording on Americans' support for welfare spending. In the treatment group, they asked respondents whether the US was spending too much (1), too little (-1), or about the right amount (0) on "welfare." In the control group, they asked the same question except that the question wording changed from "welfare" to "assistance to the poor."

-It’s really all about that Beta. The Beta coefficient represents either an increase or a decrease in the rate of ballot stuffing when the independent variable increases. For instance (see the Table), when the presence of observers increases by one unit, the occurrence of ballot stuffing decreases by .037 units, and for every one-unit increase in competition, there was a .019 unit increase in ballot stuffing. Note there is an assumed linear relationship (though different models can relax this): when X goes up by so much, Y goes up or down by so much. The ε is the epsilon or "error term," representing the remaining variation in Y that cannot be explained by a linear relationship with X.

+

-We observe Y and X in our data, but not ε. The coefficients α and β are [parameters](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parameter#Mathematical_models)---unknown quantities that we use the data to estimate.

+{width="80%"}

-A regression with one dependent variable and more than one independent variable is called a multiple regression. This type of regression is very commonly used. It is a statistical tool to predict the value of the dependent variable, using several independent variables. The independent variables can include quadratic or other nonlinear transformations: for example, if the dependent variable Y is earnings, we might include gender, age, and the square of age as independent variables, in which case the assumption of a "linear" relationship between Y and the three regressors actually allows the possibility of a quadratic relationship with age.

+

-The example table above examines how the dependent variable, fraud in the form of ballot stuffing, is associated with the following factors/independent variables: election observers, how saturated the area is, the electoral competition in the area, and the density. The regression will show if any of these independent variables help to predict the dependent variable.

+The regression table contains the following features:

-# What are the main purposes of regression?

+- **Each column is a model.** Column 1 estimates the average treatment effect of the "welfare" wording on spending views. Column 2 also estimates the average treatment effect but it additionally controls for racial resentment. Column 3 includes an interaction term between treatment assignment and racial resentment to explore how racial resentment moderates the average treatment effect.

+- **Each row contains information about a variable.** The main row of interest is *"Welfare" wording*, which shows the coefficient estimates of the treatment variable. The next row corresponds to the covariate, racial resentment, included in the regression models. The first row, *Intercept*, indicates the average value of the outcome variable when all other variables are at value zero.

+- **Each entry is the estimated coefficient.** Each entry (or the numbers within each cell of the table) corresponds to the estimated coefficient from linear regression. Information about the uncertainty of the coefficient estimates is also included below each entry. Here the standard errors of the estimates are reported in parentheses beneath each estimated coefficient. In some other cases, confidence intervals might be reported in brackets \[ \] beneath each estimated coefficient.

+- **There is additional information at the bottom of each column.** Here the authors include the sample size, residual standard error, and F-statistic for each regression model they estimate.

-Regressions can be run for any of several distinct purposes, including (1) to give a **descriptive summary** of how the outcome varies with the explanatory variables; (2) to **predict** the outcome, given a set of values for the explanatory variables; (3) to **estimate the parameters of a model** describing a process that generates the outcome; and (4) to **study causal relationships**. As [Terry Speed](https://web.archive.org/web/20151109231342/http://bulletin.imstat.org/2012/09/terence%E2%80%99s-stuff-multiple-linear-regression-part-2/) writes, the "core" textbook approach to regression "is unlikely to be the right thing in any of these cases. Sharpening the question is just as necessary when considering regression as it is with any other statistical analysis."

+# Focus on the Estimate of the Average Treatment Effect and Uncertainty of This Estimate

-For **descriptive summaries**, there's a narrow technical sense in which ordinary least squares (OLS) regression gets the job done: OLS shows us the best-fitting linear relationship, where "best" is defined as minimizing the sum of squares of the residuals (the differences between the actual outcomes and the values predicted from the explanatory variables). Furthermore, if we have a sufficiently large sample that was randomly drawn from a much larger population, OLS estimates the best-fitting line in the population, and we can use the estimated coefficients and "robust" standard errors to construct confidence intervals (see section 5) for the coefficients of the population line.^[For in-depth discussions, see: @angrist_pischke_2009, chapters 3 and 8; @berk_et_al_2014; @buja_et_al_2015; @hansen_2022] However, the summary provided by OLS may miss important features of the data, such as outliers or nonlinear relationships; see the famous graphs of [Anscombe's quartet](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anscombe%27s_quartet).

+When interpreting a regression table, the reader should focus on the row that contains information about the treatment variable. The estimated coefficient for the treatment variable tells us about the size and direction of the average treatment effect. The estimated standard errors inform us about the uncertainty of this estimated average treatment effect.

-Similarly, for **prediction**, OLS regression gives the best linear predictor in the sample, and if the sample is drawn randomly from a larger population, OLS is a consistent estimator of the population's best linear predictor. However, (a) the best linear predictor from a particular set of regressors may not be the best predictor that can be constructed from the available data, and (b) a prediction that works well in our sample or in similar populations may not work well in other populations. Regression and many other methods for prediction are discussed by @james_et_al_2013.

+In the example, Column 1 reports that the estimated average treatment effect is 0.27 and that the standard error of this estimate is 0.04. With a sample size of 1,590 respondents, the average treatment effect estimate is statistically significant at the 0.001 level, as indicated by the three asterisks beside the coefficient estimate. The positive average treatment effect estimate and the small uncertainty around this estimate provide evidence that the "welfare" wording---compared to the "assistance to the poor" wording---increased self-reported beliefs that the US was overspending on social assistance.

-**Estimating the parameters of a model** is the purpose that receives the most discussion in traditional textbooks. However, **studying causal relationships** is often the real motivation for regression. Many researchers use regression for causal inference but are not interested in all the parameters of the regression model. To estimate an average causal effect of one particular explanatory variable (the **treatment**) on the outcome, the researchers may regress the outcome on a treatment indicator and other explanatory variables known as **covariates**. The covariates are included in the regression to reduce bias (in an observational study) or variance (in a randomized experiment), but the coefficients on the covariates are typically not of interest in themselves. Strong assumptions are needed for regression to yield valid inferences about treatment effects in observational studies, but weaker assumptions may suffice in randomized experiments.^[On regression in observational studies, see: [10 Strategies for Figuring out if X Caused Y](https://methods.egap.org/guides/causal-inference/x-cause-y_en.html); @freedman_1991; @angrist_pischke_2015; @angrist_pischke_2009; @imbens_wooldridge_2009; @imbens_2015. On regression adjustment in randomized experiments, see [10 Things to Know About Covariate Adjustment](https://methods.egap.org/guides/analysis-procedures/covariates_en.html) and Winston Lin's Development Impact blog posts ([here](https://web.archive.org/web/20151024055802/http://blogs.worldbank.org/impactevaluations/node/847) and [here](https://web.archive.org/web/20151024022122/http://blogs.worldbank.org/impactevaluations/node/849)).]

+Column 2 reports that the estimated average treatment effect, when controlling for racial resentment, is 0.30 with a standard error of 0.03. Note that the estimate does not change much from Column 1. With randomization, including covariates in regression generally does not bias estimates of the average treatment effect and can often help improve statistical precision.[^1]

-# What are the standard errors, t-statistics, p-values, and degrees of freedom?

+[^1]: See for a detailed discussion.

+# Do Not Interpret Estimates on the Covariates Causally

-## Standard Error

+Because the covariates in an experiment are not randomized in the first place, we cannot interpret their coefficient estimates causally. The usual inferential challenges in observational studies, such as omitted variable bias and reverse causality, also apply to covariates in an experimental setting. In Albertson and Jessee's [-@albertson_2023] study, although the estimated coefficient for racial resentment is positive and statistically significant, we should not claim that racial resentment *caused* respondents to believe that the US was spending too much. A third variable, such as partisanship or political ideology, might drive both racial resentment and spending views. Then we might find a positive association between racial resentment and spending views through each variable's association with the third variable, even though they have no direct relationship. Individuals' beliefs about government overspending could also drive racial resentment, not the other way around.

-The standard error (SE) is an estimate of the standard deviation of an estimated coefficient.^[Strictly speaking, the **true SE** is the standard deviation of the estimated coefficient, while what we see in the regression table is the **estimated SE**. However, in common parlance, people often say "standard error" when they mean the estimated SE, and we'll do the same.] It is often shown in parentheses next to or below the coefficient in the regression table. It can be thought of as a measure of the precision with which the regression coefficient is estimated. The smaller the SE, the more precise is our estimate of the coefficient. SEs are of interest not so much for their own sake as for enabling the construction of confidence intervals (CIs) and significance tests. An often-used rule of thumb is that when the sample is reasonably large, the margin of error for a 95% CI is approximately twice the SE. However, explicit CI calculations are preferable. We discuss CIs in more detail in the next section.

+# Interpreting Regression with Interaction Terms {#sec-interaction}

-The table above from @asunka_et_al_2013 shows "robust" standard errors, which have attractive properties in large samples because they remain valid even when some of the regression model assumptions are violated. The key assumptions that "conventional" or "classical" SEs make and robust SEs relax are that (1) the expected value of Y, given X, is a linear function of X, and (2) the variance of Y does not depend on X (conditional homoskedasticity). Robust SEs do assume (unless they are "clustered") either that the observations are statistically independent or that the treatment was randomly assigned to the units of observation (the polling stations in this example).^[Robust SEs are also known as **Huber--White** or **sandwich SEs**. On the properties of robust SEs, see: @angrist_pischke_2009, section 3.1.3 and chapter 8; @imbens_kolesar_2016; @reichardt_gollob_1999; @samii_aronow_2012; @lin_2013; @abadie_et_al_2014.]

+In an experiment, researchers are sometimes interested in studying [heterogeneous treatment effects](https://egap.org/resource/10-things-to-know-about-heterogeneous-treatment-effects/). When the moderator is a variable that takes on discrete values (such as just 1 or 0), we can estimate the conditional average treatment effect---an average treatment effect specific to a subgroup of subjects. We can then estimate the interaction effect by taking the difference between the relevant conditional average treatment effects. This interaction effect is captured by the term $d$ in the regression model $Y_i = a + bT_i + cM_i + dT_i*M_i + e_i$, where $T_i$ is the treatment variable and $M_i$ is the moderator.

-## t-Statistic

+Suppose $M_i = 1$ if the subject is male and $M_i = 0$ if the subject is female. Then, the average treatment effect for males is $b + d$ and the average treatment effect for females is $b$. The difference in these conditional average treatment effects, $d$, captures how the average treatment effect differs by gender. If $d > 0$, then the average treatment effect of $T$ on $Y$ is more positive (or less negative) among males than among females. If $d < 0$, then the average treatment effect of $T$ on $Y$ is less positive (or more negative) among males than among females. If $d$ is zero, then the average treatment effects are not different between males and females.

-The t-statistic (in square brackets in the example table) is the ratio of the estimated coefficient to its standard error. T-statistics usually appear in the output of regression procedures but are often omitted from published regression tables, as they're just a tool for constructing confidence intervals and significance tests.

+# Interpreting Regression with More Than One Treatment

-## p-Values and Significance Tests

+When there are multiple treatment arms, we can estimate the average treatment effects using the following regression equation: $Y_i = a + b_1T1_i + b_2T2_i + e_i$, where $T1$ indicates the first treatment arm and $T2$ indicates the second treatment arm. There is also a control condition. By convention, $T1_i = 1$ when a unit is randomly assigned to receive the first treatment and 0 otherwise, and $T2_i = 1$ when a unit is randomly assigned to receive the second treatment and 0 otherwise. If a unit is not assigned to receive any treatment, then both $T1_i$ and $T2_i$ equal zero for that unit. This means that $Y_i = a + e_i$ when a unit is in the control group, $Y_i = a + b_1 + e_i$ when a unit is in the first treatment arm, and $Y_i = a + b_2 + e_i$ when a unit is in the second treatment arm. The average treatment effects of $T1$ and $T2$ relative to control are $b_1$ and $b_2$, respectively.

-In the table above, if an estimated coefficient (in bold) is marked with one or more asterisks,^[The use of asterisks to flag statistically significant results is common but not universal. Our intention here is merely to explain what the asterisks mean, not to recommend that they should or should not be used.] that means the estimate is "statistically significant" at the 1%, 5%, or 10% level---in other words, the p-value (from a [two-sided test](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One-_and_two-tailed_tests)^[Two-sided tests are the default in most software packages and in some research fields, so when tables do not explicitly note whether the p-values associated with regression coefficients are one- or two-sided, they are usually two-sided. @olken_2015 (pp. 67, 70) notes that since "convention typically dictates two-sided hypothesis tests," researchers who prefer one-sided tests should commit to that choice in a pre-analysis plan so "they cannot be justly accused of cherry-picking the test after the fact." @greenland_et_al_2016 (p. 342) argue against the view that one should always use two-sided p-values, but write, "Nonetheless, because two-sided _P_ values are the usual default, it will be important to note when and why a one-sided _P_ value is being used instead."] of the null hypothesis that the true coefficient is zero) is below 0.01, 0.05, or 0.1.

-To calculate a p-value, we typically assume that the data on which you run your regression are a random sample from some larger population. We then imagine that you draw a new random sample many times and run your regression for every new sample. (Alternatively, we may imagine randomly assigning some treatment many times. See [our guide on hypothesis testing](https://methods.egap.org/guides/analysis-procedures/hypothesis-testing_en.html) for more details.) This procedure would create a distribution of estimates and t-statistics. Given this distribution, the p-value captures the probability that the absolute value of the t-statistic would have been at least as large as the value that you actually observed if the true coefficient were zero. If the p-value is greater than or equal to some conventional threshold (such as 0.05 or 0.1), the estimate is "not statistically significant" (at the 5% or 10% level). According to convention, estimates that are not statistically significant are not considered evidence that the true coefficient is nonzero.

+# Other Information You Can (Often) Get out of a Regression Table

-In the table, the only estimated coefficient that is statistically significant at any of the conventional levels is the intercept (which is labeled "Constant/Intercept" because in the algebra of regression, the intercept is the coefficient on the constant 1). The intercept is the predicted value of the outcome when the values of the explanatory variables are all zero. In this example, the question of whether the true intercept is zero is of no particular interest, but the table reports the significance test for completeness. The research question is about observer effects on ballot stuffing (as shown in the heading of the table). The estimated coefficient on "Observer Present (OP)" is of main interest, and it is not statistically significant.

+Sometimes researchers provide other information for greater transparency of their data and analysis. One example is @gaikwad_2021 [p. 1140], who conducted a field experiment in India to study the impact of a door-to-door campaign to help migrants obtain a local voter identification card. They present the average treatment effects on three primary political outcomes in a regression table (see the table below). In addition to showing that the door-to-door facilitation campaign had positive and statistically significant effects on the three outcomes, they include information about the mean value of each outcome in the control group (see the row *Control mean*), the sample size (see the row *Observations*), how the standard errors were calculated (see the table note, which indicates that robust standard errors were used), and values of that the dependent variable can take (see the row *DV values*). The adjusted $R^2$ for each model is also provided in the regression table.[^2]

-It is easy to misinterpret p-values and significance tests. Many scholars believe that although significance tests can be useful as a restraining device, they are often overemphasized. Helpful discussions include the American Statistical Association's 2016 [statement on p-values](http://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108); the invited comments on the statement, especially @greenland_et_al_2016; and short posts by [David Aldous](https://web.archive.org/web/20150908143632/http://www.stat.berkeley.edu/~aldous/157/Books/stat.html) and [Andrew Gelman](http://andrewgelman.com/2015/03/02/what-hypothesis-testing-is-all-about-hint-its-not-what-you-think/).

+[^2]: This statistic is usually not very important for experiments. This is because the adjusted $R^2$ (or simply $R^2$) measures how well a regression model predicts the observed outcome, while in an experiment we are mainly interested in whether and how much a randomized treatment changes the outcome.

-## F-Test and Degrees of Freedom

+

-The bottom section of the table includes a row with the heading "F(5, 59)", the value 1.43 (the F-statistic), and the p-value .223. This [F-test](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F-test#Regression_problems) is a test of the null hypothesis that the true values of the regression coefficients, excluding the intercept, are all zero. In other words, the null hypothesis is that none of the explanatory variables actually help predict the outcome. In this example, the p-value associated with the F-statistic is 0.223, so the null hypothesis is not rejected at any of the conventional significance levels. However, since our main interest is in the effects of observers, the F-test isn't of much interest in this application. (We already knew that the estimated coefficient on "Observer Present" is not statistically significant, as noted above.)

+{width="80%"}

-The numbers 5 and 59 in parentheses are the degrees of freedom (df) associated with the numerator and denominator in the F-statistic formula. The numerator df (5) is the number of parameters that the null hypothesis claims are zero. In this example, those parameters are the coefficients on the 5 explanatory variables shown in the table. The denominator df (59) equals the sample size minus the total number of parameters estimated. (In this example, the sample size is 2,004 and there are only 6 estimated parameters shown in the table, but the regression also included many dummy variables for constituencies that were used in blocking.)

+

-# What the confidence intervals mean

+# What Your Regression Table Should Include Depends on Your Presentational Needs

-

-Confidence intervals (CIs) are frequently reported in social science research papers and occasionally shown in regression tables. They communicate some of the uncertainty in estimation: for example, the **point estimate** of the coefficient on "Observer Present" is a specific value, --0.037, but the CI (calculated as the point estimate plus or minus a **margin of error**) is the range of values from --0.09 to 0.01, implying that any value in that range is compatible with the data. (In other words, having an observer present may have reduced the rate of ballot stuffing by 9 percentage points, or it may have actually increased the rate by 1 percentage point, or the effect may have been somewhere in between.) The **coverage probability** (or confidence level) of a CI is the probability that the CI contains the true value of the parameter. Reported CIs usually have a nominal (claimed) coverage probability of 95%, so they are called **95% confidence intervals**.

-

-Coverage probabilities are easy to misinterpret. In the example table, (--0.09, 0.01) is the 95% CI for the observer effect on ballot stuffing. This does **not** mean that there's a 95% probability that the true effect was in the range between --0.09 and 0.01. Statements of that nature can be made in [Bayesian](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kNz8mfFa7nc) statistics (with posterior intervals, also known as [credible intervals](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Credible_interval)), but confidence intervals are a construct of [frequentist](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frequentist_inference) statistics. The coverage probability answers the following question: Imagine that we can replicate the experiment a large number of times, and the only thing that varies from one replication to another is which units are randomly assigned to treatment.^[The framework where "the only thing that varies from one replication to another is which units are randomly assigned to treatment" is known as **randomization-based inference**. This isn't the only framework for frequentist inference. In the classical regression framework, the only thing that varies is that on each replication, different values of ε are randomly drawn. And in the random sampling framework, on each replication a different random sample is drawn from the population. On randomization-based inference, see @reichardt_gollob_1999, @samii_aronow_2012, @lin_2013, and @abadie_et_al_2014; on the random sampling framework, see the references in note 2.] How often will the CI capture the true effect of election observers? In this framework, the observer effect is **fixed**, but the endpoints of the CI are **random**. For example, if the true effect is --0.02, then it is --0.02 on every replication. But because different units are randomly assigned to treatment on each replication, we could see the following CIs in three replications of the experiment: (--0.10, -0.01), (-0.03, 0.03), and (0.00, 0.10). The first and second CIs capture the true value of --0.02, but the third misses it. The nominal coverage probability of 95% means that in a million replications, about 950,000 of the CIs would capture the true value of --0.02. It's a claim about the **ex ante** reliability of our **method** for reporting a range, not about the **ex post** probability that the true observer effect is in the range between --0.09 and 0.01.

-

-@greenland_et_al_2016 give a helpful discussion of the benefits, limitations, and common misinterpretations of CIs. As they note, "many authors agree that confidence intervals are superior to tests and _P_ values because they allow one to shift focus away from the null hypothesis, toward the full range of effect sizes compatible with the data---a shift recommended by many authors and a growing number of journals." However, "the confidence interval is computed from many assumptions, the violation of which may have led to the results. Thus it is the combination of the data with the assumptions, along with the arbitrary 95% criterion, that are needed to declare an effect size outside the interval is in some way incompatible with the observations. Even then, judgements as extreme as saying the effect size has been refuted or excluded will require even stronger conditions."

-

-The [CONSORT Explanation and Elaboration](http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c869) document notes that in medicine, "Many journals require or strongly encourage the use of confidence intervals." In the social sciences, CIs aren't always explicitly reported; some authors report only point estimates and standard errors. If the degrees of freedom for the distribution of the t-statistic are reported, readers with sufficient technical background can construct a CI on their own (although it would obviously be more helpful if authors reported CIs explicitly). In our example table, the df for the t-statistics is the same as the denominator df (59) for the F-statistic. To construct the margin of error for a 95% CI, we multiply the SE by the appropriate **critical value**, the 0.975 quantile of the t-distribution with 59 degrees of freedom, which is 2.001 (in R, use the command `qt(.975, df = 59)`). Thus, the rule of thumb that we mentioned in the section on SEs ("the margin of error for a 95% CI is approximately twice the SE") works well here. However, if we had, say, only 20 degrees of freedom, the appropriate critical value would be about 2.09, and the 95% CI should be wider than the rule of thumb would suggest.

-

-# Watch out for "researcher degrees of freedom"

-

-

-

-The SEs, p-values, significance tests, and CIs reported in regression tables typically assume that the researchers would have made all the same analytic decisions (which observations and variables to include in the regression, which hypothesis to test, etc.) if the outcome data had shown different patterns or if (in a randomized experiment) different units had been randomly assigned to treatment. This assumption is credible if all those decisions were **pre-specified** before the researchers saw any data on outcomes or treatment assignments. Otherwise, researchers may make decisions that consciously or unconsciously tilt a study toward a desired result. This problem is known as "fishing"^[See, e.g., @humphreys_et_al_2013.], "researcher degrees of freedom,"^[@simmons_et_al_2011.] or "the garden of forking paths."^[@gelman_loken_2013.]

-

-In an instructive and entertaining paper, @simmons_et_al_2011 use simulations as well as actual experiments to show how easy it is for researcher degrees of freedom to invalidate significance tests. In simulations, they show that when researchers have unlimited discretion about which outcome to analyze, when to stop recruiting subjects, how to model the effect of a covariate, and which treatment conditions to include in the analysis, a significance test that claims to have a [Type I error](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Type_I_and_type_II_errors#Type_I_error) probability (false-positive rate) of 5% can easily be made to have an actual Type I error probability as high as 61%. In other words (and as said in the paper's title), "Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant." Allowing themselves unlimited flexibility in the data collection and analysis for an actual experiment, @simmons_et_al_2011 manage to reach the necessarily false conclusion that listening to the Beatles' song "When I'm Sixty-Four" made the subjects "nearly a year-and-a-half younger," with a p-value of .04.

-

-One remedy is for researchers to pre-specify and publicly archive their decisions about data collection and analysis (e.g., stopping rules, outcome measures, covariates, regression models, sample exclusions, and subgroup definitions) before they see the outcome data (and, ideally, before they assign treatments). Documents of these decisions are known as **pre-analysis plans** (PAPs). Critics of PAPs worry that they inhibit [exploratory data analysis](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exploratory_data_analysis). Proponents argue that deviations from the plans are not prohibited, but should be fully disclosed and highlighted, to help readers distinguish between [exploratory and confirmatory analyses](http://www.jstor.org/stable/2682991). For valuable discussions, see the symposia in [_Political Analysis_](https://www.jstor.org/stable/i23359619) (Winter 2013)^[See @humphreys_et_al_2013, @monogan_2013, @anderson_2013, and @gelman_2013.] and [_Journal of Economic Perspectives_](https://www.aeaweb.org/issues/381) (Summer 2015)^[See @olken_2015 and @coffman_2015.]. Also take a look at [our guide on pre-registration](https://methods.egap.org/guides/planning/pap_en.html).

-

-# Watch out for other possible biases

-

-Just because you use a regression to estimate a relationship does not mean that the relationship you estimate truly captures the type of relationship you are interested in. Here are some of the possible sources of bias to be aware of:

-

-* **Selection bias** can arise when there are systematic, unmeasured differences in characteristics between the individuals who are selected into the sample or the treatment and those who are not selected. In other words, selection bias can refer to either of two concerns:

-

- 1. If treatment is determined by some process other than random assignment (e.g., if subjects self-select into treatment), then treated subjects may differ from untreated subjects in ways that affect the outcome. Such differences can easily lead to bias in a regression of the outcome on treatment, even if measured characteristics of the subjects are included as covariates, because treated and untreated subjects may differ in unmeasured ways.

-

- 2. If the sample that is included in the regression isn't a random sample of the population of interest, then the regression may yield biased estimates of the population relationship between the outcome and the explanatory variables.

-

-* **Attrition bias** is a form of selection bias that can occur when outcome data are missing for a nonrandom subset of the original sample. In studies of treatment effects, attrition bias can be especially challenging to address if the treatment may have affected attrition (the loss of outcome data): when the rates or patterns of attrition differ between treated and untreated subjects, even a randomized experiment may not yield unbiased treatment effect estimates for any population.^[For more discussion of attrition bias in randomized experiments, see, e.g., chapter 7 of @gerber_green_2012.] See [our guide on missing data](https://methods.egap.org/guides/data-strategies/missing-data_en.html) for details.

-

-* Similarly, if the treatment affects the **measurement** of the outcome, the symmetry that random assignment created is threatened, and estimated treatment effects may be biased even in a randomized experiment.

-

-* **Adjustment for covariates that may have been affected by the treatment** can lead to bias, as explained in [10 Things to Know About Covariate Adjustment](https://methods.egap.org/guides/analysis-procedures/covariates_en.html).^[See also: @angrist_pischke_2009, section 3.2.3; @rosenbaum_1984.]

-

-* [**Publication bias**](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Publication_bias), also known as the file drawer problem, arises when entire studies go unpublished not because their quality is any lower than that of other studies on the same topic, but because of the nature of their results (e.g., because the results are considered unsurprising, or because they do not reach conventional thresholds for statistical significance). As Robert Rosenthal wrote in a classic article, "The extreme view of the 'file drawer problem' is that journals are filled with the 5% of the studies that show [Type I errors](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Type_I_and_type_II_errors#Type_I_error), while the file drawers are filled with the 95% of the studies that show nonsignificant results."^[@rosenthal_1979. On reforms to counter publication bias, see: @nyhan_2015; @findley_et_al_2016.]

-

-# What the R² means

-

-R² is the squared multiple correlation coefficient, also known as the Coefficient of Determination. R² shows the proportion of the variance of the outcome that is "explained" by the regression. In other words, it is the variance of the outcome values predicted from the explanatory variables, divided by the variance of the actual outcome values. The larger the R² is, the better the fit of the regression model. And a model fits the data well if the differences between the actual values and the values predicted by the regression are small. The R² is generally of secondary importance, unless your main concern is using the regression equation to make accurate predictions. It is always between 0 and 1, so if the independent variables are strong predictors, the R² will be closer to 1. It is possible, however, that a statistically significant relationship between X and Y is found even though the R² is low; this just means we have evidence of a relationship between X and Y, but X does not explain a large proportion of the variation in Y.

-

-In the example table, the R² value is .011, showing that in this case, the explanatory variables account for only a small portion of the variance of the outcome. If a model could explain all of the variance, the values predicted by the regression would always equal the actual values observed, so the regression line would fit the data perfectly and the R² would equal 1.

-

-Although R² summarizes how well the model fits the data, any single-number summary has limitations. In [Anscombe's quartet](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anscombe%27s_quartet), all four regressions have the same R², but the four graphs look very different.

-

-# Be careful when comparing coefficients

-

-If one coefficient is bigger than another, does that mean the outcome is more sensitive to that explanatory variable? No---the interpretation of coefficients depends on the scales the variables are measured on. If you convert an explanatory variable from feet to miles, the coefficient will get a lot bigger, without any real change in the underlying relationship between the explanatory variable and the outcome.

-

-# Meet the whole family

-

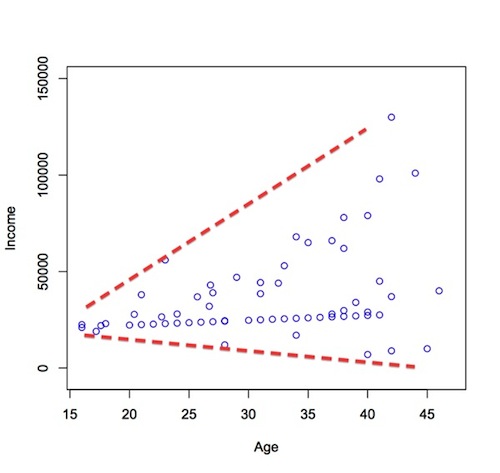

-So far, this guide has focused on ordinary least squares regression, one of the most commonly used estimation methods in the social sciences. In fact, there are many other regression methods, including weighted least squares and generalized least squares, as well as all sorts of nonlinear models for **limited dependent variables**---outcomes that are limited to a particular range of values, such as **binary** (0/1), **categorical** (A,B,C,…), or **count** (0,1,2,…) outcomes.

-

-* Researchers might use a weighted least squares regression when the variance of ε differs from one observation to another and can be modeled as a function of one or more predictors (this is called heteroskedasticity, which generally looks something like this).^[Weighting by the inverse of the variance of ε is a form of [generalized least squares](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generalized_least_squares) (GLS). The classical argument is that GLS is more **efficient** (i.e., has lower variance) than OLS under heteroskedasticity. However, when the goal is to estimate an average treatment effect, some researchers question the relevance of the classical theory, because if treatment effects are **heterogeneous**, GLS and OLS are not just more efficient and less efficient ways to estimate the same treatment effect. Instead, they estimate different weighted average treatment effects. In other words, they answer different questions, and choosing GLS for efficiency is arguably like [looking for your keys where the light's better](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streetlight_effect). @angrist_pischke_2010 write: "Today's applied economists have the benefit of a less dogmatic understanding of regression analysis. Specifically, an emerging grasp of the sense in which regression and two-stage least squares produce average effects even when the underlying relationship is heterogeneous and/or nonlinear has made functional form concerns less central. The linear models that constitute the workhorse of contemporary empirical practice usually turn out to be remarkably robust, a feature many applied researchers have long sensed and that econometric theory now does a better job of explaining. **Robust standard errors**, automated clustering, and larger samples have also taken the steam out of issues like heteroskedasticity and serial correlation. A legacy of @white_1980's paper on robust standard errors, one of the most highly cited from the period, is the **near death of generalized least squares in cross-sectional applied work**. In the interests of replicability, and to reduce the scope for errors, **modern applied researchers often prefer simpler estimators** though they might be giving up asymptotic efficiency." Similarly, @stock_2010 comments: "The 1970s procedure for handling potential heteroskedasticity was either to ignore it or to test for it, to model the variance as a function of the regressors, and then to use weighted least squares. While in theory weighted least squares can yield more statistically efficient estimators, modeling heteroskedasticity in a multiple regression context is difficult, and statistical inference about the effect of interest becomes hostage to the required subsidiary modeling assumptions. @white_1980's important paper showed how to get valid standard errors whether there is heteroskedasticity or not, without modeling the heteroskedasticity. This paper had a tremendous impact on econometric practice: **today, the use of heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors is standard, and one rarely sees weighted least squares used to correct for heteroskedasticity.**" (Emphasis added in both quotations.)]

-

-

-

-* You might see a [logit](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logistic_regression) or a [probit](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Probit_model) regression when the outcome is binary, meaning it has only two possible values: yes/no, 0/1, or True/False. Logit and probit differ in terms of the assumptions about the underlying data-generating process, but they often yield similar results.^[Logit, probit, and other limited dependent variable (LDV) models do not immediately yield estimates of the average treatment effect (ATE). To estimate ATE, one needs to compute an **average marginal effect** (or **average predictive comparison**) after estimating the LDV model (see, e.g., @gelman_pardoe_2007). Some researchers argue that the complexity of marginal effect calculations for LDV models is unnecessary because OLS tends to yield similar ATE estimates (see @angrist_pischke_2009, section 3.4.2, and the debate between Angrist and his discussants in @angrist_2001). In randomized experiments, the robustness of OLS is supported by both asymptotic theory and simulation evidence. For theory, see @lin_2013. For simulations, see @humphreys_et_al_2013 and @judkins_porter_2016. See also Lin's comments on this [_MHE_ blog post](http://www.mostlyharmlesseconometrics.com/2012/07/probit-better-than-lpm/).]

-

-* [Ordered logit](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ordered_logit) and [ordered probit](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ordered_probit) models may be used for outcomes with multiple ordered categories (such as “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “agree,” “strongly agree”).

-* [Multinomial logit](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multinomial_logistic_regression) or [multinomial probit](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multinomial_probit) models may be used for outcomes with multiple unordered categories (“Labour,” “Conservative,” “Lib Dem”).

-* [Poisson](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poisson_regression) or Negative Binomial models may be used when the outcome is a count (“how many riots this year”).

-* [Tobit](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tobit_model) models are sometimes used for non-negative outcomes (“How much time spent working this month”).

-* and many more …

-

-For the simple linear case, the coefficient tells you the change in Y you get for each unit change in X, but for nonlinear regressions the interpretation can be much more difficult. For nonlinear models you should generally expect authors to provide substantive interpretations of the coefficients. The program [Clarify](http://gking.harvard.edu/clarify) by Gary King and colleagues helps with this for Stata users; the [Zelig package for R](http://zeligproject.org/) (also by King and coauthors) supports analysis and interpretation of these models in R.

+When presenting your experimental results, your regression table should always include the treatment effect estimates alongside their uncertainty and the sample size. Apart from this general rule of thumb, what else to include in your regression table depends on your design and analysis. For example, if you estimated two regression models with one excluding covariates and another including many covariates, omitting the coefficient estimates for the covariates and replacing them with a row indicating that you have controlled for the covariates in the second regression model (e.g., "X" or "Yes" in a row named "Covariates") will focus your readers' attention on the average treatment effect estimates. If you conducted subgroup analyses, the columns should indicate the subgroup. If you used cluster randomization, report the number of clusters in addition to the total sample size.

# References

\ No newline at end of file